DeepSeek: Data Processing, A.I and Class Society

Context

To really understand how much ground DeepSeek has broken, it is necessary to first put a perspective on how these language models work.

Whenever words are submitted for processing to the A.I, they are broken down into four-letter chunks, called tokens. These tokens are interpreted by the A.I, and in the process of doing so, electricity is (obviously) consumed. The “overall price” of an A.I, when it is delivered to the consumer, is “per million tokens”, meaning every four million letters of input charges the “going rate” for usage of the model.

Hardware inherently scales to this benchmark. The less electricity is consumed, the less hardware is required for electricity to “flow through”. This means that less infrastructure, in the form of hardware, is required for the A.I to interpret text input and output text in return. The A.I, in essence, is more “efficient”, on a physical level.

This is the main advantage of DeepSeek over other company’s models. The most comparable, widely-available Language Learning Model (LLM) in the world is OpenAI’s o1 model, at $60/1M tokens. In comparison, DeepSeek offers $2.19/1M tokens. That is ~1.32% of the cost.

It is important to note that these figures are not a direct representation of how much it materially costs (not just in dollars, but in resources) to run the A.I, or produce the electronics necessary for it. There’s some factors, including profit involved— the inflated cost of OpenAI’s o1 is very much influenced by market monopoly.

However, we should keep in mind that all of this occurs on a backdrop of ardent competition between Chinese and American tech startups— the extreme figure still holds merit.

Additionally, the reaction of American investors to this, despite how fleeting they may be, is also worth taking into account. Intel, AMD, NVIDIA and the rest have all taken a hit in stocks, with the apparent fear that the overblown, overpriced electronics they produce en-masse may become “irrelevant” or “overkill”.

Material Impact

The productive output of the electronics industry have been concentrated into data centers, infrastructure that is necessary not just for generative A.I, but pretty much the entire modern world. The fact that you are reading this article right now is evidence of this.

Globally, the electricity consumption of data centers rose to 460 terawatts in 2022. This would have made data centers the 11th largest electricity consumer in the world, between the nations of Saudi Arabia (371 terawatts) and France (463 terawatts)

(…)

Market research firm TechInsights estimates that the three major producers (NVIDIA, AMD, and Intel) shipped 3.85 million GPUs to data centers in 2023, up from about 2.67 million in 2022. That number is expected to have increased by an even greater percentage in 2024.

What data centers do and “data processing” means in an actual material sense, is not even concretely understood. How much is actually dedicated to generative A.I, or any other digital category, remains a mystery.

The industry is on an unsustainable path (…) Bashir says.

He, Olivetti, and their MIT colleagues argue that this will require a comprehensive consideration of all the environmental and societal costs of generative AI, as well as a detailed assessment of the value in its perceived benefits.

“We need a more contextual way of systematically and comprehensively understanding the implications of new developments in this space. Due to the speed at which there have been improvements, we haven’t had a chance to catch up with our abilities to measure and understand the tradeoffs,” Olivetti says.

This has undoubtedly had devastating effects on the already extensive exploitation of neo-colonies around the world, and the outright destruction of the Earth itself. The idea that entire lives have been dedicated to the almighty Bitcoin, a throwaway A.I-generated image, or the facial recognition of a Palestinian, is very possible. At the same time, the actual impact of it all isn’t even measured.

We only have capital to thank for this. That an industry of this scale and importance may go so unmeasured, is a deliberate act of ignorance. After all, why measure it if it’ll draw the eye of a regulator?

DeepSeek’s accomplishment, in the face of all this, is only a drop in the bucket of what needs to be done to right the course of modern data processing. That this proportionally small shift is enough to throw the whole of the tech-related bourgeoisie into a panic is evidence of this.

Analysis

As with any major development, a considerable amount of effort is being poured into detaching the implications that this has on currently-existing class society.

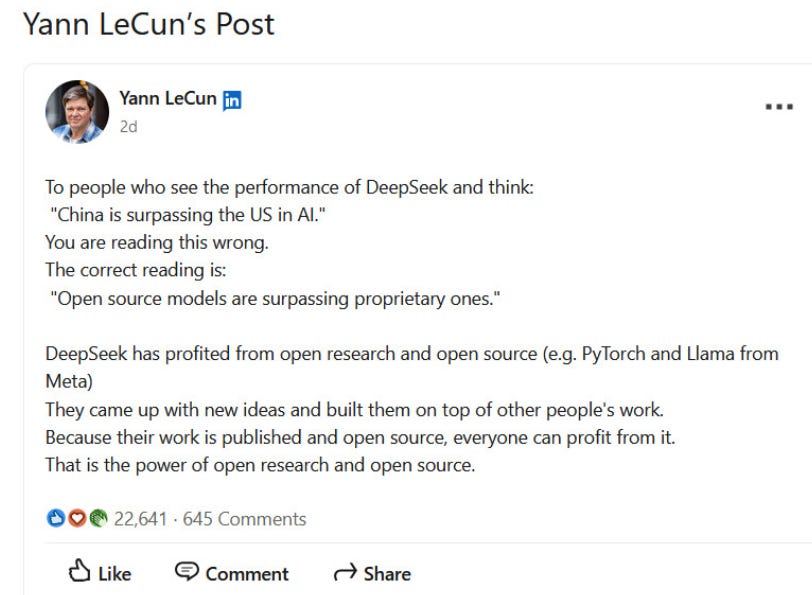

In just one example, Yann LeCun, Vice President and Chief AI Scientist of Meta, a company directly feeling the effects of the stock crash, felt it necessary to clarify the following:

On a surface level, this seems welcoming to open source software, warm even.

But this perspective entirely ignores what influences the use of proprietary or “open source” (let’s be honest, socialized) software.

If your economy is based around the use of private intellectual property, as in the United States, it then follows that proprietary software will always be the priority, with socialized software barely if ever being implemented. In such an economy, releasing privately-funded research is a no-go. On top of this, use of public-domain software inherently limits the profitability of the end product— a prospect sure to deter private investors.

One would think that someone proclaiming victory for socialized software would also appreciate it’s merits— such as the public, collaborative framework it abides by. Perhaps they would wish to implement that across broader society.

Although, given that he’s the Vice President of a $1.63 trillion dollar corporation currently getting bit in the ass by it all, it certainly makes sense that he’d take this position.

In his argument, he acknowledges that there is an incredible amount of intellectual labor involved in the field of computer science. That is clear in his defeat. He acknowledges that in order for there to be any progress, this labor must be socialized. But to socialize the industry itself? Oh no, certainly not. “Everyone” (meaning, the petit-bourgeoisie) can profit from it now, after all! Even the message is dressed up in a way so as to not even suggest that social relations lay beneath it all. The terms “open research” and “open source” abound.

Another aspect he blatantly ignores is how U.S. policymakers, financiers and tech giant OpenAI are speaking on the issue.

In a recently published “economic blueprint”, where the company discusses what policies it would like the U.S. government to implement in “furthering the development of A.I”, they write:

“Responsibly exporting … models to our allies and partners will help them stand up their own AI ecosystems, including their own developer communities innovating with AI and distributing its benefits, while also building AI on U.S. technology, not technology funded by the Chinese Communist Party.”

Even more directly, Nigel Green, CEO of deVere Group, writes:

“The balance of power is shifting, and Washington must recognise that it can’t always dictate terms to Beijing as it once did. This new reality will have far-reaching consequences for investors and policymakers”

To frame this as completely detached from the reality of geopolitics or class, while all parties involved are openly discussing and even attempting to adapt to it, is markedly dishonest.

But can we expect honesty from someone with something to lose?

How this development will affect the average person, be it in America, China, or otherwise, remains yet to be seen. Right now, hobbyists are cheering over the newfound affordability of A.I, while children in the Congo might get a break from mining cobalt with their bare hands. This is our reality.

The main observation to draw here is just how fleeting capitalism really is, in the age of computers.

That an invention on the other side of the world may spark the transference of billions to trillions of dollars, dollars that are a representation of some labor done somewhere, all in a matter of days, is not even a topic in the discussion. It is instead the people who command those dollars, and the implements that they use to get ever-so-richer, that takes center stage.

We are drawn away from pondering how such an invention may benefit humanity, or the environment, and ferried into a circus of rhetoric where crashing stocks and profit loss are our concern. An advancement in technology is seen as a “dangerous provocation” of some kind of “enemy”, as if that enemy is ours.